Microfibers Are Everywhere! Is Fabric Structure the Missing Piece?

In 2018, scientists made a startling discovery: tiny plastic microfibers, shed from our clothing, were being found inside plankton, the organisms at the base of the marine food web. Fast forward to 2025, and those same particles have now been detected in human tissues, including the brain. The idea that something as ordinary as doing laundry could put plastic on our dinner plates, or even inside our bodies, has turned microfiber pollution into one of fashion’s most urgent environmental and health challenges.

Most people know by now that synthetic fibers, such as polyester, release microplastic during washing. But what if the story does not end with fiber type? What if the structure of the fabric, whether it is knit or woven, smooth or plush, tightly bound or loose, plays just as big a role in how much material breaks away?

Knit vs. Wovens: More Than Just Fabric

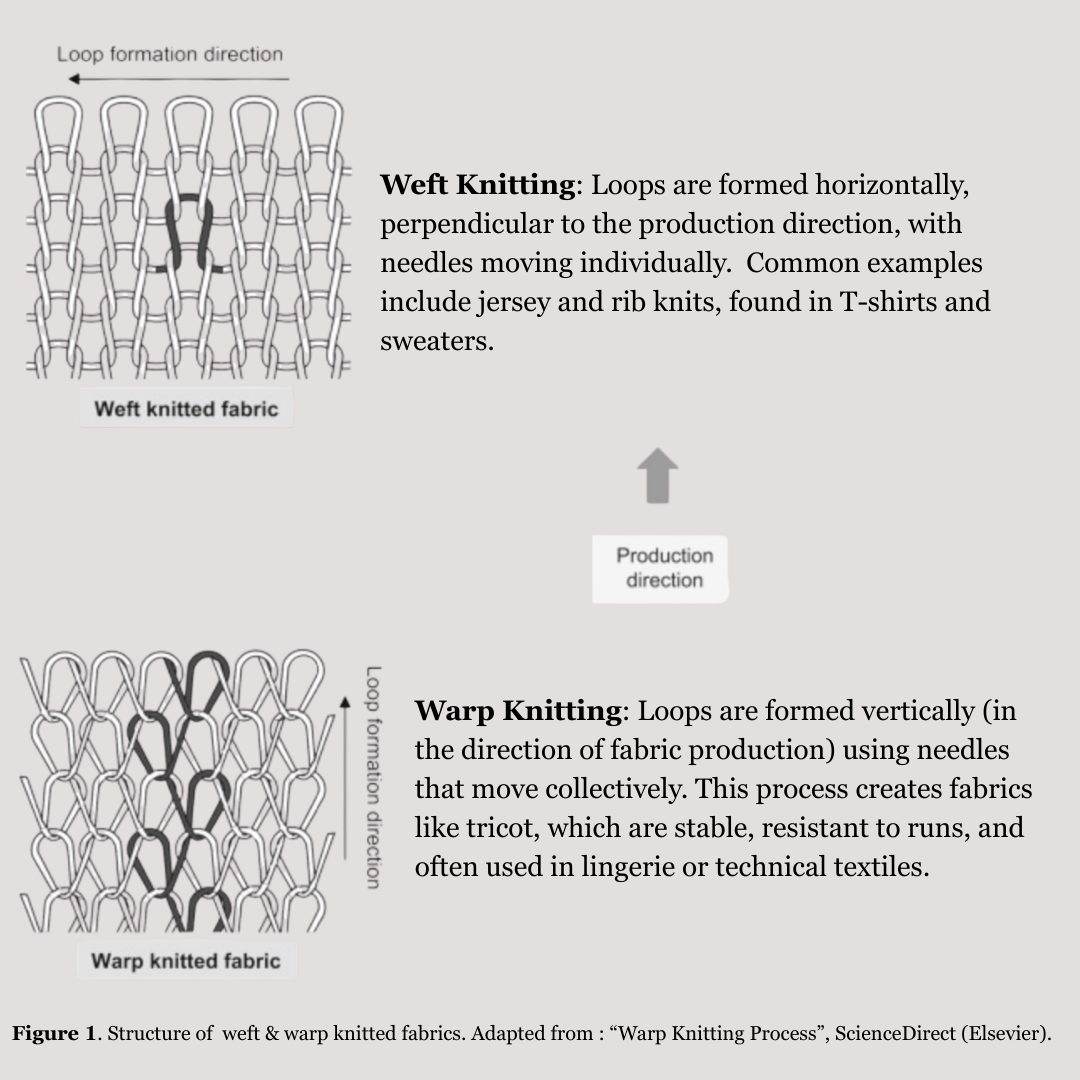

Knit fabrics are made from interconnected loops of yarn, which give them natural stretch softness. That is why your favorite T-shirts or leggings feel so flexible and comfortable. Knits come in two main forms: weft knits and warp knits.

Because of this looped structure, knit fabrics:

Have high elasticity, stretching easily in multiple directions.

Are generally lightweight and breathable, making them ideal for everyday and activewear.

Don’t fray like wovens, but edges may curl if not hemmed or finished.

Woven fabrics, on the other hand, are created by interlacing warp (vertical) and weft (horizontal) yarns at right angles on a loom. This crisscross structure makes them durable and structured, which is why denim, shirting, and upholstery fabrics hold their shape so well. Unlike knits, they have little natural stretch, fray at raw edges, and are more prone to wrinkling, but they also stand up to heavy use. There are three primary types of woven fabric: plain, twill, and satin.

Key properties of wovens:

Minimal natural stretch (unless elastic fibers are added).

Structured, durable, and shape-retaining—ideal for tailored garments.

Prone to fraying at raw edges and more likely to wrinkle compared to knits.

My Research Question

That’s where my project comes in. This past summer, under the mentorship of Dr. Izabela Ciesielska-Wrobel, an Assistant Professor at the University of Rhode Island’s Department of Textiles, Fashion Merchandising, and Design, I developed a study to explore an often-overlooked factor: how fabric structure influences microfiber shedding. Unlike most lab-heavy research that relies on expensive equipment, my work was grounded in everyday reality. I wanted to know: how do the clothes in a typical household laundry load behave?

Most studies so far focus only on fiber type, but I wanted to see what happens in the laundry room of an ordinary household, because that is where pollution really begins. Instead of relying on expensive lab setups, I cut, stitched, and prepared fabric swatches by hand, designing two washing experiments: one simulating a regular load, and another using Guppyfriend bags, a product marketed to catch microfibers. I then collected and analyzed the fibers shed to begin piecing together whether loops versus crisscrosses (knits versus wovens) change the pollution story.

This first article marks the beginning of a series in which I will guide you through my findings. Stay tuned for Part 2, where I will take you inside the methods, the hands-on preparation, the fabric selection, and the two washing techniques I used to uncover the hidden role of textile structure.