How Rising Global Trade Costs Are Reshaping Fashion in 2025

The fashion industry finds itself at a defining moment in 2025. New tariffs implemented by the U.S. government are sending shockwaves through global supply chains, forcing brands to absorb unprecedented costs while threatening years of progress toward sustainable production. What emerges is a complex reality: tariffs may unintentionally slow the pace of fast fashion, yet they're squeezing the very brands trying to build a more ethical industry.

The Scale of the Tariff Shock

The Trump administration’s 2025 tariff policies have fundamentally reshaped the economics of apparel imports. As of October 2025, the average applied tariff rate on U.S. apparel imports (HS 61 and 62) has climbed to 26.4%, nearly doubling the 14.7% rate recorded in January. This represents an ~80% relative increase on top of longstanding base tariffs that already ranged from 16% to 32% for many apparel categories.

These new “reciprocal tariffs,” imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), apply steep, uniform penalties across major sourcing countries: Vietnam faces 46%, Cambodia 49%, Bangladesh 37%, and China (34%).

The financial impact on fashion companies has been severe. Major brands report staggering costs: G-III Apparel expects $155 million in additional tariff expenses, Victoria’s Secret projects $100 million in 2025 costs, and Tapestry faces $160 million in additional costs. American Eagle anticipates $20 million in impacts in Q3 alone, rising to $40-50 million by Q4. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, tariffs could add $1.2 trillion in costs to the global fashion industry in 2025, a high end projection. More conservative U.S.-only estimates from sources such as the American Apparel & Footwear Association (AAFA) place the potential impact between $20-$50 billion. Of the global total, roughly $592 billion is expected to be passed on to consumers.

For shoppers, these tariffs translate into tangible price increases. Yale’s Budget Lab projects that clothing prices will rise 28% in the short run and remain 10% higher in the long run, with jackets and outerwear seeing increases above 24%. Across categories, average prices are up $17 in 2025.

In economic terms, these tariffs represent a modern form of protectionism, a strategy long justified by the “infant industry” argument. But in the case of sustainable fashion, the opposite is happening. Instead of protecting innovation, these tariffs risk undermining the small, ethical brands that rely on transparent, higher-cost production models.

Why Sustainable Brands Are Hit Hardest

Sustainable labels operate within fragile margins. They already pay more for fair wages, organic or low-impact fibers, traceable supply chains, and small-batch production. Sudden cost spikes from tariffs leave them little room to adapt.

Ultra-fast-fashion companies, by contrast, possess huge economies of scale and can absorb shocks by cutting corners elsewhere, shifting production quickly, or raising prices only minimally.

As Earth Day notes, “Tariffs don't distinguish between a $2 polyester shirt made in a factory with poor labor standards and a $150 organic-cotton dress made by artisans earning living wages.”

The flat-rate structure creates a lose-lose scenario: either raise prices and risk losing customers, or internalize the costs and threaten financial survival. Real-world examples illustrate this pressure:

Rumored, an eight-figure sustainable brand, saw its 400% wholesale growth collapse, forcing it to cancel major orders.

A small knitwear entrepreneur reported that a $65 stitch sample from an ethical manufacturer in Hong Kong ballooned to $179.44 after tariffs, making the business model essentially impossible.

Even before tariffs, pioneering sustainable materials like Circulose (a recycled-cellulose fiber) cost about 50% more than conventional alternatives, a disparity that contributed to Re: NewCell’s 2024 bankruptcy. Tariffs add another barrier to scaling circular innovation at a moment when the industry needs it most.

Pollution Shifting, Not Solving

Tariffs also highlight a long-standing pattern in global production: outsourcing environmental costs. For decades, wealthy countries have offshored both manufacturing and pollution to nations with fewer regulations. Redirecting production from China to Vietnam or Turkey does little to change this pattern; it simply shifts emissions geographically.

Economists warn that this dynamic fuels a “race to the bottom”, where countries lower labor and environmental standards to stay competitive. Fast fashion can adapt to this environment; small, sustainable brands cannot.

Nearshoring offers some potential relief. Shorter supply chains mean lower shipping emissions, but capacity, workforce, and cost barriers remain high.

Supply-Chain Disruption and the Nearshoring Mirage

After years spent diversifying their supply chains away from China, fashion companies now face a tariff regime that erases the advantages of the earlier strategy. Most large sourcing nations are now subject to similarly high duties.

As a result, brands are turning to Mexico, Central America, Turkey, and North Africa, regions where proximity may shorten transit times and improve oversight.

But transitioning isn’t simple:

Domestic or nearshore labor costs remain significantly higher.

Manufacturing capacity in North America is limited after decades of offshoring.

Small brands report U.S. factories charging $10,000 annual private-label fees plus $20,000 for customization, making domestic production unrealistic.

Even when garments are sewn in the U.S., raw materials (yarns, fabrics, and zippers) are still imported and subject to tariffs. As Professor Sheng Lu explains: “When tariffs drive up the cost of these raw materials, they reduce the price competitiveness of apparel made in the USA.”

Despite strong rhetoric about reshoring, the data tell a different story:

Only 40% of surveyed brands sourced from the U.S. in 2024, the same as in 2023.

U.S. textile production fell 6.2%in early 2025.

U.S. apparel production declined 4.3% in the same period.

The Fast-Fashion Paradox

While sustainable labels struggle, fast fashion’s position remains surprisingly stable. Analysts expect Shein and Temu to raise prices only 5–10%, thanks to deep supplier relationships, massive scale, and their ability to quickly reconfigure supply chains.

Still, there are signs of strain:

Shein’s IPO has been delayed amid regulatory pressure.

Temu’s U.S. sales dropped ~20% after the closure of the de minimis exemption, which had allowed duty-free imports of goods valued under $800.

Yet even these pressures haven’t slowed their global expansion. Fast-fashion production still accounts for ~10% of global carbon emissions, releases 500,000 tons of microfibers into oceans each year, and uses synthetic materials that remain almost entirely unrecycled.

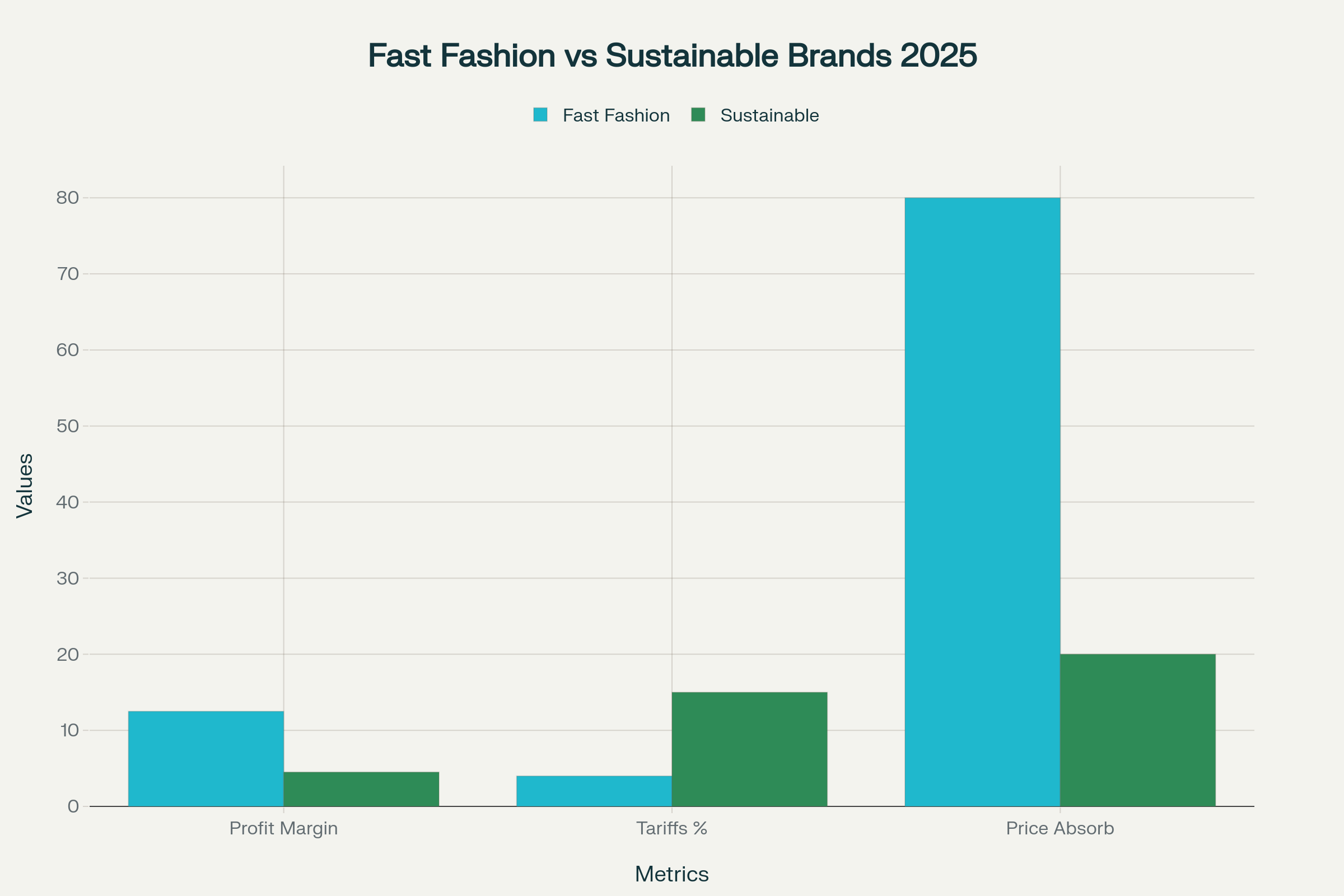

Fast Fashion vs. Sustainable Brands: Economic Resilience in 2025: This chart compares profit margins, tariff impact, and the ability to absorb price hikes, highlighting how fast fashion brands weather financial shocks far better than sustainable competitors. All figures shown are industry estimates compiled from leading market reports and public sources.

Sources:

McKinsey State of Fashion 2025; Fast Fashion Profitability Statistics 2025 (Colorful Socks); Lectra Fashion Tariff Playbook; Earth Day Sustainable Brand Analysis; Global Training Center

The closure of the de minimis exemption, which previously allowed duty-free imports under $800, was expected to devastate ultra-fast fashion business models. Yet these giants are finding workarounds: diversifying production to leverage established infrastructure and lower pre-tariff costs in countries like Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Philippines; redesigning supply chains; and absorbing hits through economies of scale. For instance, while Vietnam and Cambodia face comparable high rates (46-49%) to China's stacked duties (up to 54%), these destinations offer partial exemptions, surging capacity (U.S. imports from Vietnam rose 12.5% in July 2025), and easier redirection of excess production to non-U.S. markets like Australia, where de minimis rules persist. One concerning outcome is that tariff pressures have actually fueled fast fashion’s global expansion, sustaining high-volume output despite U.S. challenges.

This resilience means environmental damage persists. Fast fashion production accounts for roughly 10% of global carbon emissions, comparable to the entire European Union’s total. The industry releases 500,000 tons of microfibers into oceans annually, equivalent to 50 billion plastic bottles. With 60% of fashion materials made from plastic and less than 1% of textiles recycled into new clothing, the waste crisis continues unabated.

Silver Linings: The Rise of Secondhand and Green Trade Incentives

Despite their downsides, tariffs have triggered some positive shifts. Higher prices are accelerating demand for secondhand markets, rental platforms, and clothing swaps, changes that meaningfully reduce overproduction.

According to ThredUp’s 2025 Resale Report :

59% of consumers plan to buy more secondhand items if tariffs raise prices.

Among younger shoppers, the number rises to 66%.

The U.S. secondhand market has grown from $35 billion in 2008 to $230 billion in 2025, a testament to the growing appeal of circular fashion. As sustainable designer Lucy Tammam notes, “Once ultra-fast fashion costs a similar amount to a locally made, better-quality garment, consumers are more likely to choose the better option, or choose not to buy at all.”

The 2025 policy also includes emerging green trade incentives. Some fabrics made from post-consumer or post-industrial recycled content now qualify for partial tariff exemptions, and certain countries demonstrating supply-chain sustainability may receive reduced tariff rates or expedited customs clearance.

These tools, if expanded, could finally align trade incentives with climate goals.

US Secondhand Fashion Market Growth, 2008–2025: The US secondhand fashion market grew from $35 billion in 2008 to $230 billion in 2025, underscoring the mainstreaming of circular fashion and sustainability-driven consumer change.

Sources: Capital One Shopping; Persistence Market Research; Forbes; FashionUnited

What’s Still Missing

Tariffs are blunt instruments. They cannot differentiate between exploitative, low-wage factories and ethical, transparent production models. On their own, they add cost without providing direction.

What the industry needs is a comprehensive policy framework:

investment in sustainable textile R&D

subsidies for circular infrastructure

preferential treatment for verified ethical producers

stronger extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws

federal procurement favors low-impact materials

Without this, tariffs raise prices and risk eliminating the very brands leading sustainability innovation.

A Critical Inflection Point

The 2025 tariff regime marks a turning point for fashion. Rising prices may slow overconsumption and boost secondhand markets, but the brands pioneering sustainable alternatives face existential threats at precisely the moment their leadership is most urgently needed.

The irony is stark: policies meant to reshape American manufacturing may instead undermine the sustainable-fashion transition while leaving fast fashion’s dominance largely untouched.

The path forward demands more than tariffs. It requires targeted incentives, investment in circular infrastructure, and support for the brands trying to do fashion right. Without thoughtful intervention, the world risks trading one unsustainable system for another and leaving workers, communities, and the planet to bear the cost.